Being the Prologue to the Satires

Version by the University Tutorial Press Ltd, Foxton 1950

What This Is and Is Not.

In a similar fashion to other analyses, this review will only consider metrical variations in the verses. However, the common substitution of a trochee for an iamb at the start of a verse will not be analyze here. Some of Pope’s verses are what we call feminine, but I have not included all of them since many do not qualify as a metrical variation.

Pre-reading will always bring certain words to light as being slightly troublesome. However, this only occurs if the reader is intent on maintaining or forcing a pure iambic verse. In some cases this is not possible. The metrical accent and speech stress do not align and gives the reading a very unnatural sound and rhythm.

What is done here is to highlight the change of foot. There is no doubt whatsoever that Pope would have been concerned with what actual foot was being used. It would of no consequence to him at all, provided the rhythm is maintained no poet is going to be concerned about the foot.

Many would query the point of this exercise in analysis, and the short of it is that there is nothing here for the poet. This is a purely educational, academic and somewhat theoretical treatment of meter and so rhythm. The interest part is to look at the verse and see why it works. The beauty of it is that the poet would not plan it this way, it’s just how it comes along. A master like Pope has no concern for this, better to use his time writing, as should all poets irrespective of form.

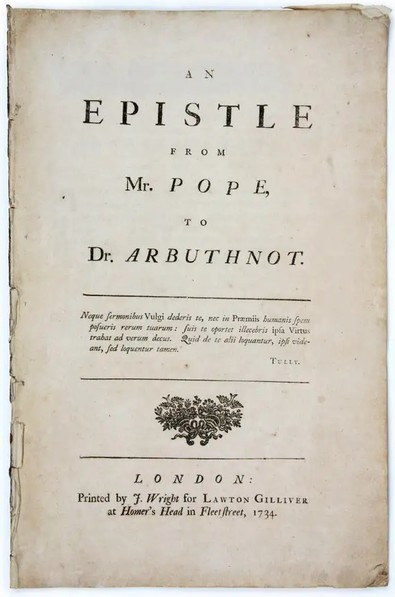

This poem is written as an epistle, but uses a dialogue form. This is indicated by the use of initials P. and A., representing Pope himself and Arbuthnot. Naturally, these letters are not sounded in the reading, but will help the reader recognize the change of voice. The subtitle is not something to take notice of as it was given by Warburton in his edition of the Poetical Works, 1751 and not by Pope.

Verse 10:

09 By land, by water, they renew the charge;

10 They stop the chariot, and they board the barge.

This couplet is interesting, not from the point of the perfection in construction, but in that the syllable count is different for each verse. Now syllable count is not necessarily important because it is the manner by which the verses are read. However, as we have already experienced, Pope is the master of the riming couplet (or heroic couplet). So how is it that this minor variation in verse 10 blends so well with its companion verse 9 and runs so well into the next verse, verse 11? There appears to be no difference whatsoever in the listening, yet we will not be able to successfully divide the verse into a series of iambs.

The companion verse is very straight forward:

09 By̆ lānd | by̆ wā | tĕr thēy | rĕnēw | thĕ chārge

We find that metrical accent and speech stress align perfectly with emphases on the relevant (important) words or syllables. Verse 10 is slightly different:

10 Thĕy stōp | thĕ chārĭŏt | ° ānd | thĕy bo͞ard | thĕ bārge

We may have been looking for a three-syllable substitution, but this would not have sat well with since the sounding and rhythm is still that of five feet. We note that the verse definitely starts with an iambic foot and finishes with two iambic feet. So what happens in between?

Some careful analysis is required for the interpretation of the middle feet. In essence, we are looking at five syllables in total, but the breakup is not as simple as a three-syllable foot and iamb. The combination does not work.

If we listen carefully at how we would naturally read the verse, we obtain a glimpse of its construction. Without a doubt there is a significant pause before and. We could say that the comma has been metrically timed, which is a possibility or we could be looking at a pause- or half-foot. Punctuation is not always metrically timed and some will debate the validity of this, but nevertheless sometimes it is and at others it is not. The foot may also be interpreted as a clipped foot, but in practice this is more common at the start of a verse. In this case the punctuation is metrically timed.

What we do find is the presence of the secundus paeon which is actually a reasonably common foot in English poetry. As we see, it sits well and accounts for the quickness in reading the second foot which cannot be matched by any other combination of feet. The five metrical accents align perfectly with the natural speech stress giving the illusion that the verse is fully iambic.

Naturally Pope would not have planned this as such, it is simply how it comes from the master of the riming couplet.

Verse 28:

27 Friend to my Life! (Which did not you prolong,

28 The world had wanted many an idle song)

Once again, we find that one verse has a minor variation. In this instance it is the second verse of the couplet. The first is as expected apart from the trochee start. This would be gauged by the end of verse 26 and indentation of verse 27, akin to a new paragraph.

27 Fri͞end tŏ | my̆ Līfe | whĭch dīd | nŏt yōu | prŏlōng

The emphasis is required on Friend for dramatic effect. Placing the speech stress on to has a very negative effect on the delivery.

For companion verse, we can consider it as:

28 Thĕ wōrld | hăd wāntĕd | māny̆ | ăn ī | dlĕ sōng

The use of the amphibrach allows the correct enunciation of wanted which we can detect by the necessity of a faster reading. Also note the trochee happily following the amphibrach and so giving the appropriate metrical accent and speech stress.

Given the manner by which we read this verse, we naturally tend to blur the two syllables of wanted along with had, the foot sounds, and indeed the verse has the iambic pentameter rhythm. The amphibrach is a valid substitution for the iamb and is capable of maintaining the rhythm in such a position, especially when followed by the trochee. A lesson to be learnt and remembered.

Verses 45 & 46:

45 ‘The piece you think is incorrect: why take it,

46 I’m all submission, what you’d have it, make it.’

I have included this couplet because unlike others which show a variation in only one verse, this mirrors the construction in both verses for an eleven-syllable count. The couplet proper is feminine in its rhythm.

45 Thĕ pi͞ece | yŏu thīnk | ĭs īn | cŏrrēct | why̆ tāke ĭt

46 Ĭ’m āll | sŭbmīs | si͝on whāt | yoŭ’d hāve | ĭt māke ĭt

In each verse, we have what is known as a feminine ending. It may appear at first that the same word is used as the ultimate rime, but we see that the rime is on the penultimate syllable as should be expected. The feminine rime is also known as the double rime, based on riming the last stressed syllable. If there are no further syllables, it is known as a masculine rime. The terminology comes from the French usage of ending in an e-mute.

As you can hear, the verses of this couplet have a very different melody to them due to their construction. It is not a variation that one would use too much or too closely, since the reader’s sense of rhythm can be easily disturbed when coming back to the rhythm proper.

Verses 49 & 51:

49 Pitholeon sends to me: ‘You know his Grace,

50 I want a Patron; ask him for a Place.’

51 Pitholeon libell’d me—‘but here’s a Letter

52 Informs you, Sir, ‘twas when he knew no better.

The name that gives us cause to look more carefully at these verses is that of Pitholeon. There are four syllables with a natural emphasis on the second syllable: Pi-thō-le-on. This in itself gives us a hint as to the first foot of the verses involved. Verse 49 becomes:

49 Pĭthōlĕŏn | sēnds tŏ | mē ° | Yo͝u knōw | hĭs Grāce

The secundus paeon starts the verse with trochees following. The pause in the third foot is due to the necessary punctuation being metrically timed, and so the foot acts as a trochee. These follow well from the secundus paeon and allows the verse to gather its rhythm and finish with iambs. The verses skips along beautifully and is in most aspects a very good match for the companion verse. Verse 51 renders as:

51 Pĭthōlĕŏn | lībĕll’d mĕ | ° ‘būt | hēre’s ă | Lēttĕr

Notice that this is not an Alexandrine, even though the syllable count may be appropriate. We can sense that there are few iambs in the verse due to the length and emphases in non-iambic positions. Once again the secundus paeon starts, but time the dactyl follows to give the appropriate emphasis. The punctuation is once again metrically time to take the place of an iamb. We note the trochees for dramatic effect, The quickness of this verse is to match it with its companion where the combination of iamb and amphibrach mirror the final three feet of verse 51:

52 Ĭnfōrms | yo͝u Sīr | ‘twās whĕn | hĕ knēw | nŏ bēttĕr

The match works well. We have the five feet, the five metrical accents and the very natural five speech stresses aligning. All of these are working together to give the sound and rhythm of iambicity.

Verses 75 & 78:

75 A. Good friend, forbear! you deal in dang’rous things.

76 I’d never name Queens, Ministers, or Kings;

77 Keep close to Ears, and those let asses prick;

78 ’Tis nothing— P. Nothing? if they bite and kick?

These verses are included not because there is any metrical variation, but as an example of the dialogue form that appears in the epistle. The interjection of A. (Arbuthnot) begins in verse 75. Even in these couplets we can sense that there are two people even if the A. and P. were not included. In some versions the initials not given, but it is still clear that the speaker has changed. Pope (P.) begins the dialogue from the very start of the epistle (verse 1).

Verse 96:

95 Whom have I hurt? has Poet yet, or Peer

96 Lost the arch’d eye-brow, or Parnassian sneer?

Verse 95 demonstrates the usual iambic rhythm which is easily worked with basically single syllable words:

95 Whŏm hāve | Ĭ hūrt | hăs Pō | ĕt yēt | ŏr Pe͞er

Of course one could also use a trochaic foot in the first if more dramatic effect is required in the reading:

95 Whōm hăve | Ĭ hūrt | hăs Pō | ĕt yēt | ŏr Pe͞er

There is a minor difference in the interpretation, but both are appropriate. As one may surmise, it is Parnassian that requires some investigation.

96 Lōst thĕ | ărch’d e͞ye | brŏw ōr | Părnās | sĭăn sne͞er

Placing either metrical accent or speech stress on the is not desirable and hence the trochee. The speed of reading does not require Parnassian as secundus paeon, but it is happily split as an iamb and anapest with the combination of sneer.

As an aside, Parnassian relates to poetry, as the concept of being poetic. It is associated with strictness of form and technical perfection. Somewhat more concerned with metrical form rather than emotion. It may be used as an adjective or noun.

It is just an amazing word to use, but it did have more meaning in Pope’s time.

Verse 153:

153 Yet then did Dennis rave in furious fret;

154 I never answer’d,—I was not in debt.

Another verse for those I may call the bean counters, those who attempt to read the verses as if they are completely made up as iambs. There are valid substitutions which allow for a slightly different rhythm for part of a verse, but this does not affect the overall iambicity of the verse.

Attempting a pure iambic construction of verse 153 leads to stumbling at furious, the syllable count will not allow it.

153 Yĕt thēn | dĭd Dēn | nĭs rāve | ĭn fū |rĭo͞us | freͯt ??

It appears to be an incomplete verse, but in reality is not.

153 Yĕt thēn | dĭd Dēn | nĭs rāve | ĭn fū | rĭŏus frēt

We find that the anapest makes it appearance for the last foot which fits the reading speed of furious. Note that both metrical accent and speech stress are aligned. The anapest allows the slightly longer verse to maintain its rhythm and match the companion verse:

154 Ĭ nēv | ĕr ān | swĕr’d Ī | wăs nōt | ĭn dēbt

which is a well constructed pure iambic verse.

Whereas we may be tempted to run with the pure iambic feet and so rhythm, it is always recommended that we pre-read to render these minor variations.

Verse 206:

205 Alike reserv’d to blame, or to commend,

206 A tim’rous foe, and a suspicious friend;

Verse 206 is rather straight forward as far as the feet are concerned. The effect of pure iambs will be to place an unnatural metrical accents and speech stresses on and a giving suspicious a rather longer sounding of the second syllable. There is also some confusion as to the emphasis placed on the first syllable.

206 Ă tīm | ro͝us fōe | ănd ā | sū̆spī| ci͝ous fri͞end

Clearly this unnatural sounding can be rectified by the use of a trochee rather than iamb. With this interpretation and reading, suspicious is enunciated correctly.

206 Ă tīm | ro͝us fōe | ānd ă | sŭspī | ci͝ous fri͞end

This combination forces the reader to a quickened pace through the final two feet. The companion verse is as expected from its reading:

205 Ălīke | rĕsērv’d | tŏ blāme | ŏr tō | cŏmmēnd

Although in a reading the change of foot in verse 206 would likely not be noticed, unless of course the iambic pentameter rhythm is being forced syllabically.

Verse 231:

231 Proud as Apollo on his forked hill,

232 Sat full-blown Bufo, puff’d by ev’ry quill;

This is only a note regarding verse 231 because it is not a metrical variation, but it could have readers stumped as to why it appears to not fit with the iambic rhythm. The answer lies in how the ending -ed was pronounced. At the time when Pope was writing, the -ed suffix was sounded and created another syllable. Today if required, we would render this differently by using the grave-e (è).

In general, the then -’d would now be -ed, and -ed would now be -èd. Thus we would write forkèd to represent Pope’s forked, and it would be pronounced as two syllables:

231 Pro͝ud ās | Ăpōl | lŏ ōn | hĭs fōrk | ĕd hīll

which is beautifully iambic.

The -ed suffix is a digraph and changes the meaning, normally to indicate the past tense and past participle of regular verbs. Today this suffix only adds a consonant sound (ed, d or t), not a syllable.

Verse 326:

326 Amphibious thing! that acting either part,

327 The trifling head or the corrupted heart,

Even with a casual reading, we will sense a quickness in Amphibious thing. These two words are read very quickly with an obvious two speech stresses. This is accounted for by the iamb and anapest with the metrical accent and speech stress arriving correctly on thing, highlighted also by the exclamation mark. The remainder of the verse consists of iambs.

326 Ămphīb | ĭo͝us thīng | thăt āct | ĭng e͝i |thĕr pārt

The companion verse is basically iambic:

327 Thĕ trī | flĭng hēad | oͯr theͯ |cŏrrūpt | ĕd he͞art

There may be some possible confusion in the third foot since we would not normally emphasize the. Yet its emphasis would give more dramatic effect and lean more to corrupted. In this case the iamb is appropriate. In a similar fashion or may be emphasized, creating the same effect. So a trochee is also plausible. However, the rhythm of the verse is more consistent with the third foot being an iamb with an increased speech stress on the.

Verse 343:

342 That not for Fame, but Virtue’s better end

343 He stood the furious foe, the timid friend,

This is the second time we have met furious. The last was in verse 153 where we found the anapest coming into play. We can safely assume a similar appearance of the anapest since here too furious is followed by a single syllable word.

343 Hĕ sto͞od | thĕ fūr | ĭŏus fōe | thĕ tīm | ĭd fri͞end

The anapest in the third foot creates as quicker reading and to the extra syllable in this foot is easily dealt with. Verse 342 is as expected being typical iambic pentameter:

342 Thăt nōt | fŏr Fāme | bŭt Vīr | tŭe’s bēt | tĕr ēnd

Verse 351:

350 The tale reviv’d, the lie so oft o’erthrown,

351 Th’ imputed trash, and dulness now his own;

This is a note on the reading and pronunciation of this verse. It is not a metrical variation.

Clearly Th’ imputed is using the elided from of the being th’. However, this is not sounded as a separate syllable. Th’ imputed is pronounced as if it were one word, thimputed. Noting this, both verses are iambic pentameter.

350 Thĕ tāle | rĕvīv’d | thĕ līe | sŏ ōft | o’ĕrthrōwn

351 Th’ ĭmpūt | ĕd trāsh | ănd dūl | nĕss nōw | hĭs ōwn

Verse 386:

386 Unspotted names, and memorable long!

387 If there be force in Virtue, or in Song.

A casual reading of this verse will have us place and unnatural stress on the third syllable of memorable to fit with the iambic rhythm. It does not make a great deal of difference, but does add something odd to the pronunciation. The verse renders as:

386 Ŭnspōt | tĕd nāmes | ° ānd | mēmŏraͯ | bl͝e lōng

Keeping with the natural speech stress, memorable has the dactyl for the first three syllables, and so avoids the unnatural and drawn our third syllable. It is unlikely that the cretic would appear in this foot due to unnatural stress. In this instance memorable does not take the primus paeon as one may be expecting.

386 … mēmŏră | bl͝e …

The other point of concern for the reader is that the comma is metrically timed for the iamb. Dramatic effect in the reading would require an emphasis on and both in terms of metrical accent and speech stress. So in this case, not technically a pause-foot.

The companion verse merrily skips along as a series of iambs:

387 Ĭf thēre | bĕ fōrce | ĭn Vīr | tŭe ōr | ĭn Sōng

Verse 400:

400 By Nature honest, by Experience wise,

401 Healthy by temp’rance, and by exercise;

Simply by our reading we notice that the verse sounds to have some symmetry about it. We should also remember that this cannot be done with a purely iambic verse. So what is occurring here?

400 By̆ Nā | tŭre hōnĕst | ° bȳ | Ĕxpērĭ | ĕnce wīse

The effect is created by the two amphibrachs, one either side of a metrically timed comma. The result is that by the time we have overcome the metrical pause, it sounds like the verse has been split exactly in half.

The companion verse does not have a metrically timed comma due to the more pronounced iambic rhythm.

401 He͞althy̆ | by̆ tēmp | ‘rănce ānd | by̆ ēx | ĕrcīse

There are a few points to note with this verse. The beginning is a trochee foot which would be expected merely from the follow on from the previous verse. In the third foot, and has both metrical accent and speech stress to impart the importance of the inclusion of both temp’rance and exercise. Finally, there is a minor promoted stress on the last syllable of exercise, but this would scarcely be noticed.

Verse 410:

410 With lenient arts extend a Mother’s breath,

411 Make Languor smile, and smooth the bed of Death,

From an initial reading, generally we would not stumble with this verse unless purposely forcing the iambic rhythm. (Yes, there are some who read verse-by-verse, require a syllable count of ten and force the iambic rhythm.)

We note that it all comes together, but we should also be able to tell that we have glossed quickly over lenient arts, and for a reason:

410 Wĭth lē | nĭĕnt ārts | ĕxtēnd | ă Mōth | ĕr’s bre͞ath

By itself lenient would come as dactyl with its natural speech stress. However, it is not in the correct position to take on the dactyl foot. Instead, the anapest is found in the second foot which would make sense. The anapest provides a spritelier rhythm or a quicker sounding. All this allows us to keep the overall iambic rhythm, which is the only requirement.

As is mostly the case, the companion verse skips along as pure iambic.

411 Măke Lān | guŏr smīle | ănd smo͞oth | thĕ bēd | ŏf De͞ath

Ferrick Gray

August, 2024

Green Iamb Publications

an imprint of

xiv lines